Exhibition with Peter Kozak at Kunstbunker ARI

Dulled Feeling, Aishla Manning, 2018, digital print

Structural Being

Aishla Manning and Peter Kozak 'Soft Blow', by Kat Campbell

Manning and Kozak’s exhibition Soft Blow is a balance of duality. We asked the artists to create works responding to the KUNSTBUNKER space, the groundwork of a downstairs area that was never developed. The two Brisbane based artists responded to this with the concept of ‘foundation’ in its varying forms.

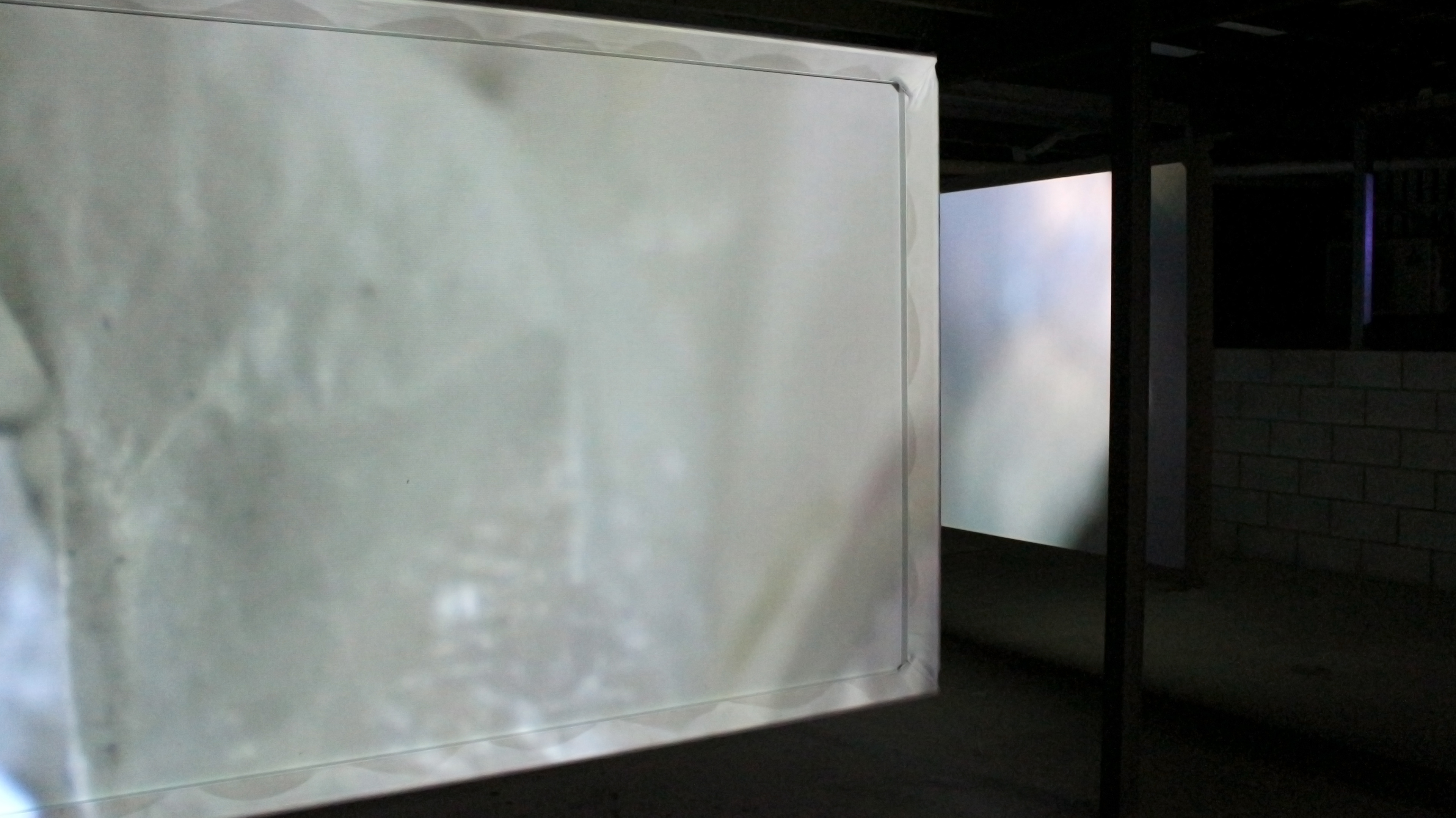

Kozak’s piece is a two-channel video of a plastic Subway bag that the artist found stuck in tree branches by the Bunya Crossing Reserve. Two suspended screens display different angles of the plastic bag, going in and out of focus and stability. The overcast, and creek-water-softened imagery of grey and brown wet stones and branches, contrasts with the weathered white plastic bag. In this way, it is easy to draw initial and simplistic conclusions of the disparity between nature and humanity. However, what becomes clearer as you watch the diptych is that these images are not there to make a statement on the environment. Instead the contrast of images displays how the accidental and unnoticed can become central to an image. Kozak’s work centres the plastic bag in order to humanise it; the audience, then, is encouraged to conceive the plastic bag as a memento of personal experience, rather than a comment of humanities affect on nature.

While developing this show, Kozak related a moment that steered his work towards exploring the accidental, how these occurrences affect a story, an object, or—more specifically—a person. The anecdote was his grandfather building his home. During construction, Kozak’s grandfather killed a snake with a shovel. Its body ended up in the cement mixer, which later became part of the house’s foundation. Kozak explained how the house was later built up upon it, entombing a moment that was a part of its formation. Watching the plastic bag in the videos becomes an act of contemplative reverie. Memory is delicate and fading, but to the individual, it feels permanent. The bag is a signifier of the random events that later become formative experiences. Kozak looks at the fragility of our personal narratives, and how small and unexpected occurrences can change the course of our lives and our memory—how parts that seem small or insignificant change the course of our private reality and identity.

When you enter the space, Manning’s work presents itself as an anthropomorphic monument. It is a large timber cube, held together precariously with clamps. Within it, a rope attached to the scaffolding suspends a leaf blower, sporadically blowing itself in circles. The dominant gust of the leaf blower assaults the lumpy white pillow layering the inside of the cubed timber walls. The leaf blower is on a timer: roughly every 15 minutes it begins its barrage, as though it has its own free will. The noise is starling, abrupt and irritating. It disrupts the conversation and concentration of viewers, and the lumpy material within the structure can barely remain attached to its surface. In this way the work, using functional tools and materials, is virtually collapsing on itself.

A word that is often used within Manning’s practice is ‘futility’. To observe this work is to perceive the uselessness and absurdity of such a design to the point of humour. Looking at domestic tools, materials, and spaces, each item is engineered for a purpose: to provide security and comfort. When combined and haphazardly engineered the work becomes a failure by design, and the viewer relents to and accepts this. Uselessness, especially when purposeful, is inherently funny in the realm of objects. When it comes to actions, futility becomes distressing. Pillows are objects of comfort, but they are also used to cushion the effects sound. But ultimately, despite the walls being covered by them, the pillows act as a failed soundproofing for the leaf blower. The domesticity of the items prompts us to consider the household—how it is both a refuge from volatility, and a home to it. The home, and what goes on within it, is sociologically the framework from which we develop. Manning’s work is an innocent and failed way to silence something, like a child with their eyes closed and their fingers in their ears.

Both Kozak and Manning’s works connect in a space of memory, and the moments that become our foundations. The use of building materials in conjunction with personal subject matter in both works speaks to this notion of foundations, in equal yolks, being a solid and stable structure as well as a fragile and intangible basis of our identities.